Guido Reni is one of the foremost artists of the Bolognese school. Learn about his rendering of the four gospel writers from the founder of M&G, Dr. Bob Jones, Jr.

Search Results

The Four Evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

Oil on Canvas, 1630s

Guido Reni

Bolognese, 1575-1642

The painter of this elegant series of the Four Evangelists is Guido Reni. Reni is not only one of the most revered 17th-century painters but also one of the Baroque era’s most fascinating personalities. His friend Carlo Cesare Malvasia wrote an illuminating biography acknowledging the painter’s paradoxical character. Although deeply religious, Reni was plagued by an addiction to gambling; although renowned for his generosity, he was notoriously thin-skinned, and although labeled conventionally “prim,” he was one of the few artists of the time willing to mentor female painters (most notably Elisabetta Sirani). Regardless, throughout his life Reni is said to have “cut an impressive aristocratic figure, always fashionably and expensively dressed and usually attended by servants.”

Born in Bologna in 1575, Reni began his training in the studio of Denys Calvaert. In his late teens, he entered the Carracci Academy where he continued studying until 1598 when he embarked on an independent art career. Despite his initial success, he soon realized that to expand (and solidify) his reputation he would have to study in Rome. He left for the “eternal city” in 1601, and for the next thirteen years he immersed himself in Rome’s rich artistic heritage. He returned to Bologna in 1614 and remained there for the rest of his life. His thriving Bolognese studio received commissions from all over Europe, and Ian Chilvers notes, “Rubens was the only contemporary painter who had a more glittering international clientele.”

Reni’s 1611 Slaughter of the Innocents reflects the tight brushwork, pristine finishes, and rich coloration of his early work. While in Rome, he did flirt briefly with the popular Caravaggesque style (as seen in the Crucifixion of St. Peter). However, he soon returned to his classical roots. David Steele observes that as his style continued to mature, “his colors become progressively more silvery and his brushwork more free.”

We see evidence of this tonal shift and looser brushwork in M&G’s gospel writers—particularly in the renderings of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. The more vibrant coloration of the St. John figure relates to his iconography. This “beloved disciple” is often dressed in red and green garments (red symbolizing his love for Christ and green representing his faith in the resurrection.) Also apparent in the upper right of John’s canvas is an eagle; this identifier symbolizes the “soaring inspiration” mirrored in the artful imagery that opens his gospel and illuminates his book of revelation. This attribute is derived from the “four living creatures” surrounding God’s throne (referenced in both Ezekiel and Revelation). Each of the gospel writers has an identifier related to these tetramorphs as they are called: Matthew’s is the angel (clearly visible in his portrait), Mark’s is the lion (in the lower right of his canvas), and Luke’s the ox (faintly visible in the upper right of his portrait). Irenaeus of Lyon was the first to associate these mystical creatures with the four gospel writers, but it was the Church Father Jerome who assigned each their specific identifier.

By the end of his life, Reni had become the most famous Italian painter of his day. His style is still regarded as “perfectly poised between formal precision and expressive density” (Baroque Painting, p. 82) Although he briefly fell out of favor during the 19th century, his reputation as the “divine Guido” remains firmly intact.

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Published in 2019

-

Christ Cleansing the Temple, Luca Giordano, called Luca fa presto (1634–1705)

-

Christ Disputing with the Elders, Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti (1571–1639)

-

Madonna and Child, Carlo Dolci (1616–1687)

-

St. James the Greater, Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

-

St. John the Evangelist, Domenico Zampieri, call Il Domenichino (1581–1641)

-

St. Matthew, Guido Reni (1575–1642)

-

The Body of Christ Prepared for Burial, Cavaliere Giovanni Baglione, called Il Sordo del Barozzo (1566–1643)

-

The Repentant St. Peter, Carlo Dolci (1616–1687)

-

The Return from the Flight into Egypt, Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari (1654–1727)

The Italian Baroque paintings, comprising an astounding 105 works, form the core of the M&G collection and provide a survey of styles and artists that is unsurpassed in the United States. Beginning about 1590, artists made a conscious effort to break away from the artifice of Mannerism. The mannerist emphasis on the design and decorative aspects of art resulted in paintings that failed to communicate. With the onset of the Protestant Reformation (1517) and the subsequent reaction of the Council of Trent (1545–63), the Catholic Church looked to artists to produce painted propaganda that would help regain their influence over the populace.

A Sibyl

Oil on canvas

Ginevra Cantofoli

Bolognese, 1618-1672

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

From the Middle Ages to the early Renaissance, an artist’s instruction commonly occurred in the workshop of master painters or religious orders; however, in the 13th century, the craft guild system launched an apprenticeship program to carefully regulate the training, materials, and assessment of prescribed artistic techniques. The standard training began for boys (around 13 years of age) within a master’s workshop setting, which lasted 3-7 years; this process became the required expectation as outlined in Cennino Cennini’s, The Craftsman’s Handbook, a how-to-guide to artistic techniques, “If you do not see some practice under some master, you will never amount to anything, nor will you ever be able to hold your head up in the company of masters.”

Once completing the basic preparatory skills, the youth could progress to “journeyman” (a master’s assistant) by possibly journeying to another city to study and practice under a different master at a new level of training and collaboration. After 3-4 years (sometimes longer), he was allowed to submit a test piece to be evaluated by both his own master and other guild representatives. If his “masterpiece” passed, he would then be able to work as a “master” painter himself and acquire a permit to establish his own workshop and apprentices—hence the name, Old Master painters.

During the Renaissance, a new concept of artistic training developed known as The Academy—a private, informal instruction venue that not only developed artistic skill, but also included life observation, philosophy, and discussion to increase knowledge and broaden understanding.

These various methods of training were challenging for artists, but produced some well-known greats as well as some very gifted lesser known artists. While art education was well framed, suited to males, and even strictly regulated in areas, there were yet some options for a female to pursue training and have a presence in the world of art. One historian states, “Although there were routes to follow for a man who wanted to be an artist and no map at all for a woman, art training was more flexible than it seemed on the surface.” Even when excluded from apprenticeships and academies, history provides many examples of women that received artistic training through private tuition or lessons (if her family had money), from an artist-father in his workshop, in a convent, or from seeking out friendly advice.

Interestingly, a number of the known female painters spring from Bologna, Italy in particular. It was a city where women outnumbered the men and a place that prided itself for its famous university which as early as the 13th century opened its doors to women (some of whom became lecturers renowned for their scholarship).

Elisabetta Sirani, grew up in Bologna and under the tutelage of her artist-father, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who (somewhat reluctantly) trained her in the manner of his master, the “Divine Guido” Reni. She became a respected painter and received important commissions for churches and portraits. She became a member of “merit” as a full professor and a member of “honor” of the Academy of St. Luke in Rome—one of the first women painters and the only Bolognese of her generation to enjoy this privilege. Since she was officially recognized as a professional artist, she could direct her own studio, take on apprentices, and train young artists. Breaking the tradition based on the model of arts education for men and women, Sirani welcomed women of all ages and backgrounds in her atelier including amateurs and aspiring artists like Ginevra Cantofoli, who went on to make a reputation of her own.

Ginevra Cantofoli is believed to come from a well-to-do family and was older than her teacher; yet, she was one of Elisabetta’s favorites and possibly became one of her assistants. She based many of her works on her teacher’s, and subsequently, some of her works have been confused as Sirani’s. However, she also produced original works including those for the Foresti family chapel and other large scale compositions for churches in Bologna. Rare for the 17th century, she earned her living as a professional artist; this is confirmed by a legal document drafted by the artist herself in 1688 in which reference is made to “money by her earned by her work of painting.”

A sibyl in classical mythology is a female prophetess often pictured with a book or scroll and which symbolized the harmony between Christian and Classical ideals. However, this work is unusual as a self-portrait of Ginevra who blends the classical sibyl and Hebrew prophetess. By painting a sibyl, she associated herself with areas where women had little influence during the time, such as ancient literature and languages and religious painting.

Based on history and the great numbers of male Old Masters that followed the accepted training processes, it is unusual to see works by female Old Masters; however if you visit M&G, you can see at least two examples on display in the collection including this unique self-portrait.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2014

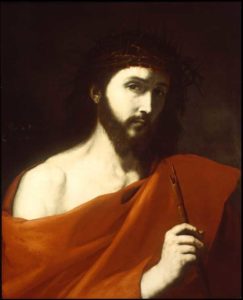

Ecce Homo (Behold the Man)

Oil on canvas, Signed and dated middle left: Jusepe de Ribera español/ F.1638

Jusepe de Ribera, called Lo Spagnoletto

Spanish, active in Naples, 1591-1652

Ribera was born in Javita, Spain and presumably apprenticed in his homeland until he sailed for Naples, Italy in 1607, where he first observed the works of Caravaggio and developed an early affinity for the master’s style. Caravaggio’s art was a continual influence throughout Ribera’s career, but a trip to Rome provided exposure to the classical style of the Carracci and Guido Reni. Ribera’s impressive list of collectors includes Cosimo II, the Viceroys of Naples, and King Philip IV. He always considered himself a Spaniard (hence, the identification in the present signature) and greatly influenced the art of his homeland although he lived in Italy most of his life and made a considerable impact on Italian Baroque artists.

The present Ecce Homo is a devotional picture boldly presenting Christ after his torture and mockery by the Roman soldiers. Ribera painted the work in 1638 at the height of his popularity, and it illustrates his ability to combine a strong spiritual image with poignant realism. Christ gazes at the viewer with a confidence amidst the mockery, knowing that the crown of thorns and reed-scepter are emblems of a heavenly power unrealized by mankind. The empty background, isolation from the jeering crowd, and the engaging look of Christ’s eyes all contribute to create an arrestingly moving portrait of the highest order.

“El Greco to Goya” is the earliest known exhibition in which this painting participated—a 1963 show held at the John Herron Museum of Art in Indianapolis, IN and at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island. Additionally, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, TX hosted an exhibit in 1983 including M&G’s Ribera. Two of the foremost American scholars on Spanish paintings, Craig Felton and William Jordan, produced a corresponding exhibition catalog in which M&G’s painting is referred to as “unquestionably the finest” of Ribera’s known works of this subject.

John M. Nolan, Curator

Published in 2014

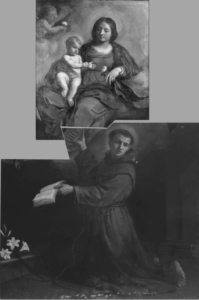

St. Anthony of Padua

Oil on Canvas, 1658

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Il Guercino

Cento, 1591–1666

Long before social media, opinions were influential. And, in art history, opinions have affected perspectives toward artists and their work for entire generations. One example of this is the brilliant philosopher of the Victorian era, John Ruskin, who was an art critic that championed JMW Turner, Britain’s greatest landscape painter. Ruskin preferred and praised the contemporary artists of his day such as Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, the art prior to Raphael, and the Gothic style.

In contrast, Ruskin’s opinion about the Italian Baroque period can essentially be summed up by his reaction to one painting in the Brera Gallery in Milan by Guercino, “partly despicable, partly disgusting, partly ridiculous” (Ruskin, p.203). He classified many of the great seventeenth-century painters within what he labeled “the School of Errors and Vices” (Ruskin, pp.144-45). Such strong views influenced the collecting habits of collectors and museums in Europe and America for several decades. Consequently, Baroque artists are still recovering from the stigma; their names are not as well-known as the Renaissance masters even though their skill is of equal quality.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Il Guercino was one of the most important and talented painters of the Italian Baroque period. He hails from the region of Emilia-Romagna, born in the small town of Cento, which is close in proximity to the artistic centers in Ferrara and Bologna. He was largely self-taught (influenced by works of Ludovico Carracci and Caravaggio), although he studied with local artists Paolo Zagnani and Benedetto Gennari.

Guercino’s nickname means squint-eyed or cross-eyed possibly due to an eye condition, yet this disability didn’t seem to affect his work. Ludovico Carracci praised him in Bologna, and his “genius was recognized by the Bolognese canon Padre Antonio Mirandola, who became his earliest protector and obtained the artist’s first Bolognese commission in 1613” which established his career. “He was then patronized by the papal legate to Ferrara, Cardinal Jacopo Serra,” Duke of Mantua Ferdinando Gonzaga, and the Bolognese cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi, who later become Pope Gregory XV— summoning Guercino to Rome in 1621 (de Grazia, p.157).

Following the pope’s death in 1623, Guercino returned home to Cento to work, painting a wide range of subjects and drawing countless distinctive studies in red chalk and ink. As an artist, he was truly inventive, a real creative. He would put his ideas to paper very quickly and spontaneously—something his biographer Malvasia described as guizzanti, meaning “dart with a flick of a tail, as fishes” (Brooks, p.12).

Among other requests, he was asked to become official painter to the courts of England (1626) and France (1629 and 1639). After the death of his archrival Guido Reni in 1642 he moved his studio to Bologna. By the 1650s, his European patronage had tapered to more local commissions, which is when M&G’s painting was made.

St. Anthony of Padua features the thirteenth-century Doctor of the Church, who was born in Lisbon. He joined the Franciscan Order (represented by the dark brown robe and tonsure haircut) and became a close friend and follower of Francis of Assisi. He had a vast knowledge of scripture and was a gifted preacher, serving in France and Italy including Bologna and Padua, where he died. After his death, he was made the patron saint of Padua.

In art, Anthony is depicted in various scenes describing events from his life. M&G’s subject is the vision of the Virgin and infant Christ—a common theme during the Counter Reformation. The vision came while Anthony was in his room, and he is portrayed with a book (which identifies his learning), lilies (representing his purity), and a crucifix (in the shadows above the lilies).

At the time of acquisition in 1973, M&G’s founder knew that this painting was referenced in the artist’s account books—it was one of two St. Anthony altarpieces recorded. The great Guercino and Baroque specialist, Sir Denis Mahon wrote Dr. Bob, “I have no doubt whatsoever from studying the painting itself that it is an authentic late work by Guercino…. It was the lower half of a picture which had been very much bigger…. It follows that the picture is likely to have originally been a full-size altarpiece” (M&G files).

In the 1990s, Richard Townsend found that of the two St. Anthony altarpieces referenced in Guercino’s account books, one was still in Verona and the other cut in two and sold. This work remained a mystery, until recent years when Italian art historian Enrico Ghetti pieced together the history based on the confusing details in Guercino’s Book of Accounts and Malvasia’s biography. M&G’s painting was once called the Madonna and Child with Saint Anthony of Padua and paid for in 1658 by Pier Luigi Peccana (from Verona) most likely on behalf of the Marquis Gaspare Gherardini. The altarpiece used to hang in the Chapel of Saint Antony at the Capuchin church of Verona.

Ghetti suggested the painting, Madonna with Child, which was formerly in the Sgarbi collection in Italy is most likely the upper portion of our work; he has proposed a reconstruction of the dismembered altarpiece as seen here.

M&G’s painting reveals some of the standard matters art historians encounter regularly: the influence of art critics like John Ruskin, the connoisseurship of art specialists like Sir Denis Mahon, dismembered altarpieces, and confusing primary records for art scholars like Enrico Ghetti to ferret out. More importantly, this interesting work represents one of the most notable and innovative Italian painters of the seventeenth century.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Bibliography

Brooks, Julian. “Characterizing Guercino’s Draftsmanship.” Guercino: Mind to Paper. Getty Publications: Los Angeles, 2006.

De Grazia, Diane. “Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, Called Il Guercino.” Italian Paintings of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington: New York, 1996.

Ghetti, Enrico. 2020. “La ricostruzione di una pala del Guercino: la Madonna col Bambino e sant’Antonio d Padova per i Cappuccini di Verona,” Storia dell’ Arte 153, Nuova Serie 1.

Ruskin, John. Modern Painters (vol. ii), ed. Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. George Allen: London, 1903.

Ruskin, John. Ruskin in Italy: Letters to His Parents, 1845, ed Harold I. Shapiro. Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1972.

Published 2025

The Rest on the Flight into Egypt

Oil on canvas

Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari

Roman, 1654–1727

Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari was born in Italy in 1654. Scholars still dispute Chiari’s origins with some believing he was born in Lucca and others Rome. With encouragement from his mother, Chiari learned the foundations of painting around the age of 10 from Carlo Antonio Galliani. He moved on at the age of 12 to study under the well-known Carlo Maratta, who drew inspiration from the classical style of Raphael and the Renaissance. Chiari’s earliest documented work, Venus with a Hermit, was dated 1675. Sadly, the work is lost.

Chiari was active in the late-Baroque period. His body of work displays the characteristics of both the High Baroque style as well as the Rococo which is reflected in his color choices. His paintings exhibit the influences of Annibale Carracci, Guido Reni, Cortona, and Andrea Sacchi. While he clearly drew inspiration from his predecessors, he took those ideas and transformed them into his own. His early commissions consisted of frescoes for various churches and chapels in Italy, and he also helped prepare cartoons for mosaics that would later be installed in St. Peter’s Basilica. Perhaps his most important client was Pope Clement XI who commissioned Chiari to paint St. Clement, the pope’s patron saint, most likely for the Basilica San Clementi. This led to an ongoing patronage by the Albani family (of whom the pope was a member). He also served as the director of the Academy of St. Luke from 1723-1725.

The landscape and composition of M&G’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt show similarities to both Chiari’s Christ and the Samaritan Woman and Adoration of the Magi. In this scene, Mary and Christ are seated on a plant-carpeted rock beneath the shade of a palm tree. Mary (wearing her signature colors of red and blue) wraps a comforting and supporting arm around Christ while holding a book in her opposite hand. Christ reaches out to obtain some of the fruit foraged and offered by Joseph. Several putti arrange the palm branches to provide the maximum amount of shade to cool the weary travelers. Another putto dangles from the left of the tree passing dates to be put in the basket held by the two below him, and a young angel kneels in front of the Holy Family offering a jar of water from the small brook at Mary’s feet. To the right of Joseph in the background, two angels appear deep in conversation as they tend to the donkey.

Chiari nods to his possible birth city through the Romanesque architecture in the distant town. Chiari’s work beautifully illustrates a scene of refreshment and reminds the viewers that even the Holy Family too needs time to rest and refuel.

M&G’s painting has an interesting provenance as it was once owned by the Earls of Dunraven from Adare County in Limerick, Ireland and possibly displayed in the family’s Clearwell Castle in Gloucestershire, England. It was probably in the collection at Adare Manor, principal home of the earls until the manor’s sale by the 7th Earl of Dunraven in 1982 to a family from Florida. Today, it is a luxury hotel. M&G’s painting was purchased in a 1982 Christie’s auction by renowned art dealer, Julius Weitzner. Dr. Bob Jones, Jr., a close friend of Weitzner, was able to acquire the painting for the Museum & Gallery where today it serves as a beautiful representation of Roman Baroque painting.

Rebekah Cobb, M&G Registrar

Published 2022